The Private World of Public Officials: Evidence about the political activities of public servants in Canada

by Brendan Boyd and Andrea Rounce

Public servants are expected to be impartial in democracies like Canada. As unelected officials hired and promoted based on merit, public servants must be non-partisan and provide objective advice to elected governments of different political stripes. They must also deliver public services and programs to citizens free from favouritism and corruption. Ultimately, public servants must demonstrate that they are not partial to one party or one set of citizens over others.

Our previous research revealed that, while there is consensus among elected officials, the public, and public servants about the necessity of impartiality at work, there are differing opinions about whether and how public servants are expected to be non-partisan in their private lives. In Osborne v. Canada (1991), the Supreme Court established that a complete ban on political activity, including supporting or donating to political campaigns, violated public servants’ constitutional rights. Federal and provincial governments now have rules in place for how and why public servants can exercise their political rights, including a range of activities they may undertake. Some activities require permission from the Public Service Commission, including when public servants may want to run in a provincial or federal election. Approval for these requests is usually contingent on the public servant’s position, type of work, and profile. If they receive this approval, they take a leave of absence from their job and resign their position if they are elected. In a few cases at the federal level, public servants have been prevented from running for office as a condition of their employment. Emilie Taman lost her job as a federal prosecutor when she ran for office for the NDP in the 2015 federal election. In 2017, the Federal Court of Appeal ruled that the federal Public Service Commission acted unreasonably by denying her a leave of absence to run. Even if public servants do not engage in formal party politics, the nature of their job requires that they exercise restraint in their personal activities and communications so it does not affect their ability to do their jobs, or the public’s (or elected officials’) perception of that ability.

Of course, the criteria for what affects a public servant’s ability to do their job is not easily defined and has been the subject of an ongoing debate. Clarke and Piper argue for a direct connection between a public servants’ political activity and their job performance. They suggest that public servants’ ability to participate in online political activity should be determined by the level and nature of a public servant’s position, the visibility of the online activity, the substance of the online activity, and the identifiability of the online actor as a public servant. Savoie has argued that, despite legal interpretations, any political activity will jeopardize a public servants’ ability to impartially carry out their duties. In his view, “regardless of what the Supreme Court might say, public servants should not become political actors, especially in the middle of campaigns…They are not political actors. We have political actors; they are politicians…If you start handing out flyers and you appear in videos, you become a part of that — you become partisan."

These debates have real world implications. In 2015, a government scientist at Environment Canada was suspended and eventually retired after his song protesting the Harper government went viral on YouTube leading up to the federal election. In 2022, questions were raised when some public servants may have used government emails while donating money to the trucker convoy that occupied downtown Ottawa and several border crossings. These are just two high-profile examples, but public servants across Canada are continually faced with the challenge of determining what is appropriate political behaviour in their private lives. How do elected officials, members of the public, and public servants, themselves, draw the line?

Based on a survey of nearly one thousand public servants at all levels of government in Canada, our previous research found that three-quarters believe they can be politically active outside of their work while ensuring an effective and legitimate government.[1] But the published study did not break down differences among public servants; that is the gap that this research note fills.

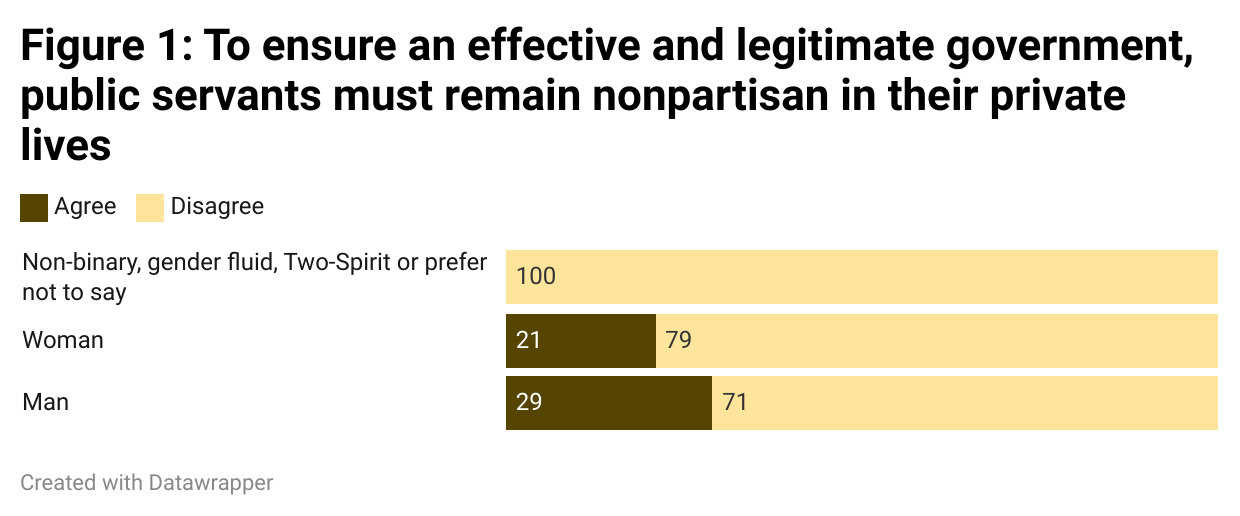

For this note, we compared public servants’ attitudes about political activity outside of work based on gender, age and type of role. In our sample, women (79 percent) were slightly more likely than men (71 percent) to disagree that public servants should be non-partisan in their private lives (Figure 1). All of the public servants who identified as non-binary, gender fluid, Two-Spirit or preferred not to say disagreed that public servants must be non-partisan outside of work.[2]

We compared the attitudes towards political activity outside of work for different age groups of public servants as well. Silent Generation/Baby Boomers were slightly more likely than Millennials and Generation X to agree that public servants must remain non-partisan outside of work (Figure 2). However, there is no evidence that public servants lower their expectations for being politically active outside of work as they get older.[3]

We compared public servants’ attitudes towards political activity in their private lives according to their position. Executive managers (47 percent) were the most likely to agree that public servants should be non-partisan outside of work (Figure 3), while senior managers (30%), managers (20%) and those not in management (19%) were less likely to agree. These findings suggest that the higher a public servant’s position in management, the more likely they are to believe that public servants should be non-partisan outside of work.

We explored what type of political activity public servants engage in and how frequently. We asked public servants how often they have, or how likely they would be to engage in different political activities. Almost all public servants, 99 percent, indicated that they often have, probably would or always have, or always will vote in elections (Figure 4). Other forms of political activity were less common. Public servants were less likely to indicate that they would get/have been directly involved in the partisan political process, with 85 percent saying they were unlikely to join political parties and 86 percent saying they were unlikely to donate money to political parties. However, public servants were slightly more likely to undertake other activities like joining lawful demonstrations (21 percent) or donating to interest groups (22 percent). Finally, 16 percent of respondents indicated they often have, probably would or always have, or always will join boycotts.

Conclusions

Overall, a strong majority of public servants believe they can engage in political activities outside of their work. The analysis indicates that gender and age are not strong indicators of how public servants will view their ability to engage in political activities outside of their work. Public servants in executive management positions are more likely to agree that public servants should be non-partisan in their private lives compared to those who are in lower-level management positions or not in management. This is perhaps not surprising as executive management positions typically require more restrictions on political activities compared to managers and those not in management. Still, a majority of respondents in all position categories disagreed with the idea that public servants should be non-partisan in their private lives.

Despite strong support among public servants for the ability to engage in political activities in their private lives, they were not likely to be politically active outside of voting. Public servants seem to be more concerned about protecting their political freedoms in principle than exercising them in practice. One explanation for the discrepancy is that public servants are more concerned about their freedom of speech, including the ability to express their opinions freely and participate political discourse, than their capacity to engage in formal political activities. We did not ask public servants specifically about their participation in online political activities, since we were more interested in the overall frequency of political activity than the specific forum in which they occur. Some of the included activities, such as joining boycotts or demonstrations, could take place on the internet and through social media, however we do not capture public servants participating in political discussions and debates online and through social media. We did not include this as it is not a formal political activity and respondents may have different ideas about what type of discourse would be categorized as political. Cooper examined the online activity of public servants and found that unionized public sector employees were less likely than the average citizen to engage in online political activity and in particular activities involving official political campaign material.

The analysis raises several questions for future research. What impact does the political activities of public servants have on perceptions of their impartiality and their ability to do their job, on the part of elected officials and the public? Is there more capacity for public servants to engage in the political process without compromising a key principle of the public servant’s role? In addition, is there a difference between partisan political activity and general political activity? Would a public servant’s support of a particular cause or organization be viewed differently than support or membership in political party?

Methodology

The survey was conducted in spring 2021. It was sent by email, in English and French, to public servants at the federal, provincial, territorial and municipal level. The survey was distributed through the Institute of Public Administration of Canada’s (IPAC) membership list as well as a survey panel of Canadian public servants. In 2021, IPAC had over 1,600 members and the survey panel was made up of 1,500 public servants. We received 992 responses in total from both distribution methods. For the first three figures which included only those working in Westminster systems of government in Canada, we analyzed 830 responses.

[1] The data here includes public servants working at the federal, provincial and territorial levels in Westminster systems in Canada (public servants working at the municipal level and in NWT and Nunavut were not included because they do not work in systems involving party politics).

[2] The number of respondents who described their gender as non-binary, gender fluid or Two-Spirit or preferred not to answer was about 5% of total respondents. While the number is small, we included the category in the chart above to provide a fuller representation of gender identities.

[3] The number of Generation Z survey respondents was too low to include in this note.

Might be the very 1st time I’ve seen this TOPIC examined via ‘Canadian social media !

For a Non Partisan Senior watching as Yellow ‘conservative’ Media expands its Daily & Incremental Cognitive/ Narrative Warfare on everyday Canadian ‘perceptions -> beliefs .. what should I assume ? What should one ‘expect ? Such ‘media deploys every single ‘Propaganda Tool’ in the Partisan ‘conservative’ Political ToolBox - to incrementally ‘GROOM public perceptions

This is the Era of the Contemporary Coup D’Etat - Capture the MEDIA & the Palace is Yours !

Yellow Media now - IS The Narrative .. the Daily ‘MASSAGE’ - & no longer ‘the messenger

🦎🏴☠️🍁