By: Evan Walker and Jared Wesley

This research brief is produced by the Common Ground Team. The data is drawn from campaign period and post-election surveys conducted as part of the Consortium on Electoral Democracy (C-Dem) study, which is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

INTRODUCTION

In a province used to electoral landslides, Alberta’s most recent election was an anomaly. As the dust cleared on May 29, 2023, the incumbent United Conservatives (UCP) retained control of government, holding 49 of 87 legislative seats. Fourteen seats changed hands to the New Democrats (NDP), mostly in the cities. Several races decided were by only a few hundred votes. Given the closeness of the election, questions remain as to what motivated voters to cast their ballots for either of the two main parties.

The C-Dem surveys offer us a unique opportunity to dissect the vote, testing several leading theories about why Albertans voted the way they did.

Here are our main takeaways:

1. While voters favoured the NDP to handle social issues and the environment, the UCP had an issue advantage when it came to what mattered most to voters, namely inflation/affordability.

2. The NDP made significant inroads among conventional conservatives, winning the support of about 1-in-5 Albertans who identified as conservatives, placed themselves on the right side of the spectrum, or typically vote for conservative parties.

3. Compared to the UCP and Danielle Smith, the NDP and Rachel Notley made a more positive impression on voters.

4. Partisanship in Alberta has a huge impact on perceptions of the provincial economy. NDP voters hold a much more negative perception of the economy compared to UCP voters.

5. New Democrats and United Conservatives are divided on a host of issues, including their views on the provincial political establishment, Confederation, and economic justice.

6. Few Albertans switched their vote throughout the campaign period, with most of the change in vote intention occurring in the inter-election years.

In this post-mortem, we examine several leading explanations for the election outcome:

1. Issues: Did more voters trust the UCP to handle the issues that mattered most to them?

2. Leadership: Was Danielle Smith the preferred choice for premier, ahead of Rachel Notley?

3. Performance: Did Albertans approve of the UCP’s handling of government and the economy?

4. Values: Did the UCP align with more voters ideologically?

5. Identity: Did the UCP hold an advantage when it came to deeper forms of voter allegiance?

Our attention then turns to determining the most important factors driving people to vote for the UCP versus the NDP. We weigh the importance of demographic and attitudinal drivers, finding that a significant portion of vote choice came down to attitudinal differences. In particular, disaffection with Alberta’s political establishment and a strong sense of economic justice and national identity proved strong predictors of NDP vote-likelihood. Regionalism, exclusionary attitudes, and oil protectionism were strong predictors of the UCP vote.

Within our demographic model, working in the public sector, having more education, and living in a city positively impacted NDP vote-likelihood. In contrast, being male, having a higher income, and being more religious positively impacted UCP vote likelihood. However, after accounting for political attitudes, only work sector and degree of urbanization remained significant predictors of vote-likelihood.

ISSUE ADVANTAGES

Many observers point to issue ownership as a leading explanation for election outcomes. Simply put, the party that voters trust most to handle the issues that matter most will win the election.

Throughout the 2023 Alberta campaign, the two leading parties focused attention on different sets of issues. For the UCP, the economy was front and centre, specifically maligning the NDP's previous economic record and playing on the widespread belief that conservative governments are best for Alberta's economy. Likewise, the incumbent UCP made promises to be tougher on crime and provide further buffers against the cost-of-living crisis through lower income taxes and a moratorium on personal and business tax increases without a referendum. The UCP also positioned itself as the party to protect Alberta's interests from federal intrusion and remain a staunch defender of Alberta's oil industry, frequently drawing parallels between Rachel Notley and Justin Trudeau.

In addition to criticizing Danielle Smith’s leadership capacity, the Alberta NDP positioned itself as a defender of Alberta's public healthcare and education systems against further UCP mismanagement. The NDP also promised to tackle affordability through proposals to eliminate small business taxes, impose utility rate caps, and plans to expand affordable housing. Both parties also released varying climate plans to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

How did voters view which party would best handle these and many other issues?

Figure 1 illustrates each party’s issue ownership. Results are retained for those who selected the NDP or UCP, with the small portion of voters who selected other parties for each issue omitted. The dotted line extending upwards from the 50 per cent mark indicates which party has an advantage on each issue. Every bar extending to the left of this line in blue is an issue advantage for the UCP, and those extending to the right in orange comprise an issue advantage for the NDP.

Figure 1: Issue Advantages by Party

Most respondents indicated that the New Democrats best handle education, healthcare, housing, immigration, and environmental issues. The UCP retained slimmer advantages in terms of defending Alberta's culture and interests, crime and justice, and the economy.

This pattern suggests the New Democrats may have made new inroads into issues typically perceived as conservative strengths.

However, this is only part of the story. Our pre-election survey also included a write-in option for voters to identify the issue that was most important to them in the upcoming election. Figure 2 captures these responses under various broad groupings.

Far and away, the issues at the forefront of Albertan's minds were healthcare, affordability, and the economy.

While the most prominent issue on Albertan's minds was healthcare, affordability was a close second and, notably, was not included as an option in the questions evaluated in Figure 1.

It is worth discussing how our affordability group differs from our economy grouping, as the two are closely related. Our "affordability" grouping captures all responses about inflation, price gouging, utility rates, housing, and income supports. In comparison, our "economy" grouping concerns economic growth and recovery, fiscal management, and job creation. Combined, just over 40% of Albertans found these issues to be the most important, challenging the notion that healthcare was the leading issue in the 2023 provincial election.

Figure 2: Most Important Issue

Figure 3 illustrates which party was most trusted on each issue displayed in Figure 2. Particular attention should be given to healthcare, affordability, and the economy, the top three issues for Albertans in this election. While the NDP held a sizeable advantage in healthcare, education, climate, and leadership, only one of these, healthcare, was a "top 3" issue for Albertans—albeit the largest singular category from Figure 2. On the other hand, the UCP came out on top in 5 of our major issue categories and, most importantly, edged out the NDP when it came to handling the economy and affordability. The UCP also held the largest advantages regarding protecting oil and gas and advocating for Alberta's place in Confederation.

Figure 3: Most Important Issue Advantages by Party

In sum, while the NDP may have been favoured across a variety of major issues (Figure 1) when it came to the most important issues facing Albertans, the UCP held a slight advantage, coming out ahead in 5 of 9 major issues. It also implies that while NDP commitments to introduce new tax credits, tax breaks, and affordability measures may have helped close the ownership gap on those issues, it was not enough to sway the large percentage of voters that identify the economy as the most important issue to them.

While the NDP may have been viewed as better suited to handle issues such as healthcare, when it came to the economy and affordability, the second and third most pressing issues on Albertans mind respectively, the UCP pulled ahead.

PARTY LEADER IMPRESSIONS

Another publicized storyline throughout the 2023 election was the resurgence of Danielle Smith. Smith has long been a controversial figure in Alberta politics, from crossing the floor as leader of the Wildrose Party in 2014 to more recent gaffes regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine War, and healthcare.

Across the aisle, opposition leader Rachel Notley was also no stranger to Albertans. During the NDP's tenure in office, opposition to the controversial Bill 6 and rising public debts amidst economic woes generated their fair share of protest and pushback from Alberta's farmers and more fiscally conservative voters. Given this baggage, it is difficult to say definitively that either leader has fully captured the hearts and minds of the Alberta electorate heading into the 2023 election.

One way to visualize how Albertans feel about these two parties and their leaders is through a density plot, where lower values represent " dislike" and higher values "like" of them. The peaks and valleys displayed in Figure 4 represent how Albertans felt about the two parties heading into Election Day. Across the electorate, the UCP was less well-received than the NDP, with more respondents indicating they "really dislike" the UCP than the NDP. Likewise, while neither party had large numbers of respondents that indicated they "really liked" either party, the NDP did obtain a larger share of respondents on the upper portions of the 0-100 scale.

Figure 4: Density Plot of Party Impressions Across All Voters

Figure 5 reveals similar sentiments about each party leader.

Rachel Notley made a more favourable impression across all voters than Danielle Smith. However, neither was overwhelmingly well-liked.

A large proportion of voters place both party leaders towards the "really dislike" section of the scale, although Danielle Smith seems to have made a significantly worse impression on voters than her counterpart.

Some of this is likely explained by the basic fact that politicians are among the most disliked professions across the general population. However, the story gets more interesting if we break the data down into how partisans viewed their party leader.

Figure 6 splits our data into UCP and NDP partisans. Unsurprisingly, most partisans have an affinity for their party leader; however, this enthusiasm is slightly less amongst United Conservatives. For UCP voters, a greater share is relatively lukewarm on Smith's leadership, as the apex of Smith's approval peaks much earlier than Notley (around 75 on our scale) and tapers off thereafter. Conversely, Rachel Notley is looked upon more favourably by NDP supporters than Smith is by United Conservative supporters, with the greatest concentration of NDP partisans placing Notley at around 90 on our 100-point scale.

Figure 5: Leader Impressions Across All Voters

Figure 6: Partisan Impressions of Party Leaders

Different patterns can be observed when examining how rural and urban Albertans viewed each party leader. Figure 7 replots the distributions from Figure 5 but splits the data into rural and urban respondents. More rural respondents dislike Rachel Notley compared to Danielle Smith; all the same, a greater share of rural Albertans holds favourable views of Smith over Notley until the very upper portion of our scale. In other words, Smith is overall positively received among the rural crowd, but Notley does seem to have a few stalwart supporters in rural areas.

Still, the most significant gap in leader impressions occurs amongst the urban population. Our plotted distribution indicates that most urbanites "really disliked" Danielle Smith compared to Rachel Notley, with the latter receiving the greatest share of positive impressions among urbanites than any other sub-grouping.

Overall, if the UCP held a small advantage over the NDP in terms of issue ownership, the New Democrats held a similar-sized edge on issues of leadership.

Figure 7: Party Leader Impressions Rural Vs. Urban Divide

INCUMBENT GOVERNMENT PERFORMANCE

A third approach to understanding election outcomes focuses on retrospective voting. According to this theory, voters are outcome-oriented and tend to reflect upon the government's last four years when casting their ballots. We can think of this as a "performance review" for the incumbents, mainly concerning matters of the economy. In other words, many voters internally evaluate "what have you done for me lately" or “am I better off now than four years ago” when assessing the party in power. If the government has not done very well, voters may push for change.

In practice, it is seldom so straightforward; retrospective assessments are often filtered by other factors, such as whether the party in power is of the same political stripe as the voter. In these cases, the incumbents might be granted some leeway. Correspondingly, if the party in power is of the opposite political ideology as the voter, the incumbents may be viewed on more negative terms. Therefore, objectively evaluating the incumbent government's performance can be difficult for the average voter.

Figures 8 and 9 capture this dynamic well. Two stark patterns emerge when we break the data down into partisan assessments of the UCP government. For NDP supporters, over 90% were "not very or not at all satisfied" with the UCP. On the other hand, only about 20% of UCP voters were dissatisfied with the UCP government, with the majority (around 55%) indicating they were "fairly satisfied".

Figure 8: Partisan Assessment of Government Performance Under Danielle Smith

Similar patterns can be found when we examine perceptions of economic performance by NDP and UCP supporters. Figure 9 depicts UCP and NDP supporters' views of Alberta's economy in the run-up to the election. Unsurprisingly, these two groups were quite split when assessing the economy. For NDP supporters, 55% felt the Alberta economy had worsened, while only 17% felt the economy had improved. On the other hand, UCP supporters held a much more favourable view of the economy; roughly 46% felt the economy had improved, while only 29% felt it had worsened.

When assessing how the current UCP government handled the economy, over 60% of NDP supporters felt current government policies had made the economy worse, whereas 53% of UCP supporters felt current policies had made the economy better.

Figure 9: Partisan Assessment of Economic Performance Under the UCP

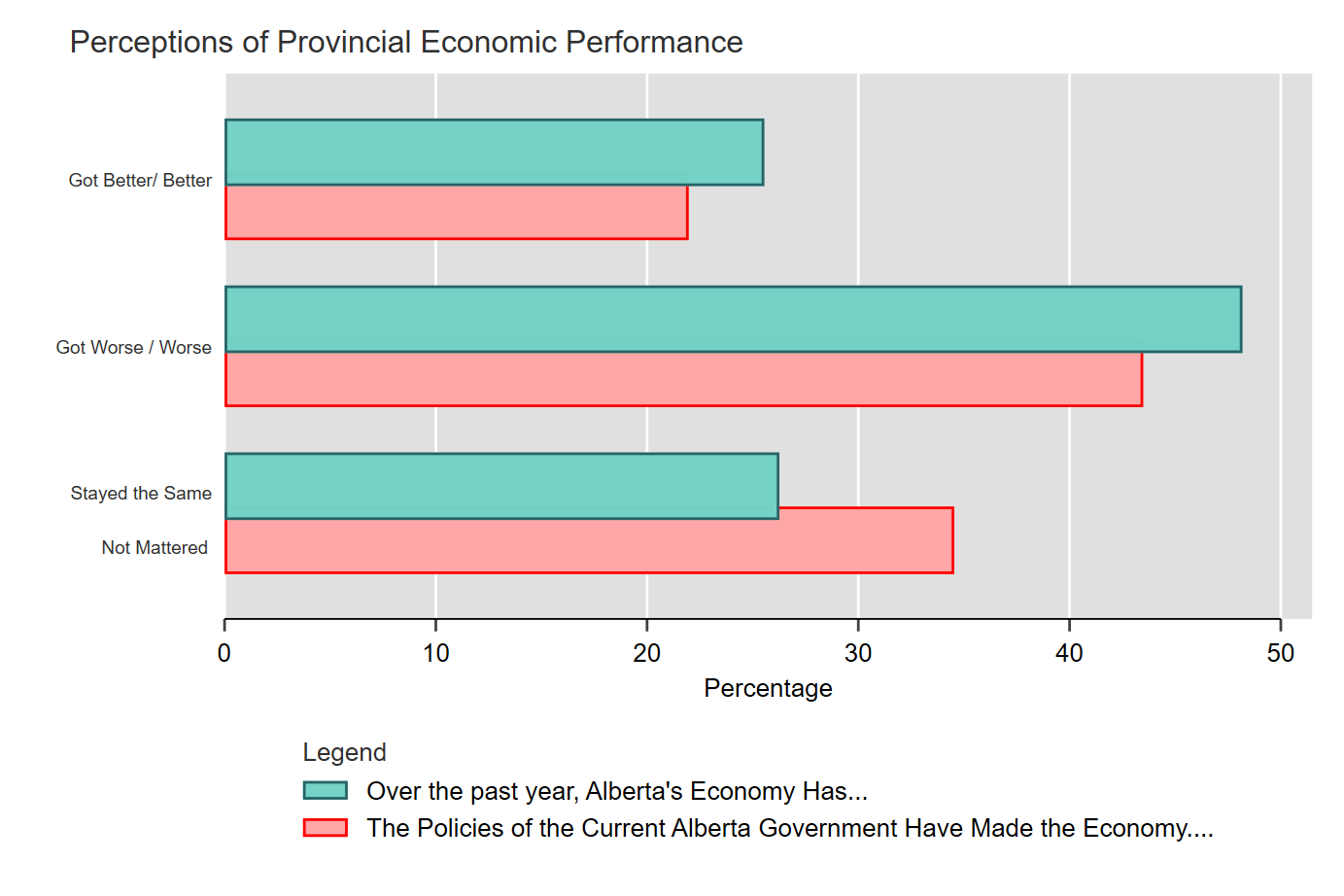

Figure 10 displays how all respondents, not just UCP or NDP partisans, felt about the economy. For all voters, the bad still outweighs the good. Around one-quarter of Albertans felt the economy had improved and that the current government’s policies had strengthened the economy. Conversely, almost half felt the economy had gotten worse, with just over 40% placing the blame for these economic woes at the feet of the UCP government.

Figure 10: Perceptions of Economic Performance (All Voters)

Some voters may not always tie their vote to the state of the broader economy but instead vote based on their finances; given the increasing cost of living crises, we might expect most respondents to feel the squeeze.

Figure 11 illustrates how NDP and UCP supporters felt about their personal finances and how the policies implemented by the UCP government have impacted their pocketbooks. Consistent with their negative economic outlook, 44% of NDP supporters felt their finances worsened over the past year, with fewer than 10% stating their financial situation had improved. Predictably, 48% of NDP voters felt that the policies of the UCP government had worsened their finances, while another 49% felt UCP policy initiatives had made no difference; less than 5% found the government's policies to have had a positive impact. These findings are consistent with how NDP voters felt about the economy in Figure 9.

When it comes to UCP supporters, things get a bit more complex. As a group, United Conservative voters appear to distinguish between broader economic forces and their own personal finances. When asked about their own pocketbooks, UCP supporters have felt the sting nearly to the same extent as NDP supporters, with 38% of respondents feeling their finances had worsened and only 14% expressing that they had improved. This contrasts with 46% of UCP supporters who had stated that the economy had improved over the past year (Figure 9). Likewise, only 23% of UCP respondents felt the UCP government’s policies positively impacted their financial situation, despite 53% stating that the UCP government’s policies had positively impacted the economy.

These findings suggest that UCP supporters are seemingly less likely to associate their personal finances with the overall state of the economy.

Nearly an equal percentage of NDP and UCP supporters have felt their finances worsen; however, this has seemingly not impacted how UCP supporters feel about the broader provincial economy. Additionally, fewer UCP supporters felt the Alberta government's policies had a tangible benefit on their financial situation than the economy writ large.

Figure 12 summarizes how all respondents felt about their financial situation. Only a tiny percentage of Albertans felt their finances had improved over the past year, while nearly 90% expressed their finances had either worsened or stayed the same.

Figure 11: Partisan Assessment of Personal Finances

Figure 12: Personal Financial Perceptions (All Voters)

When it came to evaluating government performance and the economy, NDP and UCP partisans had drastically different perceptions of the incumbent government’s performance. Undoubtedly, partisanship is animating perceptions of economic reality.

ELECTION PREDICTIONS, VOTE PREFERENCES, AND STRATEGIC VOTING

An interesting storyline throughout the 2023 campaign trail was the NDP’s attempt to appeal to disaffected United Conservatives' scepticism of Danielle Smith’s leadership. Several old-guard progressive conservatives publicly espoused their support for Rachel Notley, with some calling on all “moderates” that usually vote conservative to lend her their vote. To what extent was this effective? Was there a significant block of “orange Tories” driving up the NDP’s vote share?

One way to assess these questions is by visualizing the percentage of “right-leaning” voters that voted for the NDP. Figure 13 groups our respondents into three categories, based on a scale numbered 0-10, where political centrists are assumed to be those placing themselves in the middle of the scale (five), values below five indicate the person is left-leaning, and values over five indicate the person leans to the political right. We can then plot what percentage of these three groups voted NDP or UCP.

Results suggest that the NDP did succeed in appealing to some ideological conservatives, with approximately 25% of right-leaning Albertans indicating they had voted for the NDP. Likewise, the NDP remained popular among “centrist” Albertans, with around 60% siding with the New Democrats. Similar shares of those who identify at the federal level with the CPC (20%) also broke for the NDP at the provincial level (Figure 14). Conversely, only about 5% of federal progressives (Liberal, NDP, or Green) supported the UCP.

Figure 13: Vote Choice By Ideological Stance

Figure 14: Federal Party ID and Provincial Vote Choice

Another interesting metric to examine is what party voters indicated as their second choice. We might think of this as another means of examining how the NDP appealed to UCP voters and vice-versa; were many torn between these options or stalwart in their opposition to the “other”? Our breakdown points to the latter; in fact, less than 15% of UCP and 10% of NDP supporters indicated that they would place their political opposition as their second choice.

In fact, for the UCP, over 40% expressed that their second vote choice would be Wildrose Independence, with roughly another 30% siding with the Alberta Party. For NDP voters, the largest proportion (40%) indicated they would vote for the Liberal Party of Alberta, with roughly another 20% indicating they would vote for the Alberta Party.

Among the less prominent political parties, most Liberal Party supporters designated the NDP as their second choice. A slightly larger share (35%) of Alberta Party supporters indicated their second choice would be the United Conservative Party, roughly 10 percentage-points more than the percentage of Alberta Party supporters who indicated the NDP would be their second choice (25%). Wildrose Independents were primarily split over the UCP or Alberta Party as their second choice, with the largest share (45%) choosing the UCP. Figure 15 captures these patterns in greater detail.

Figure 15: Second Vote Choice by Primary Vote Choice

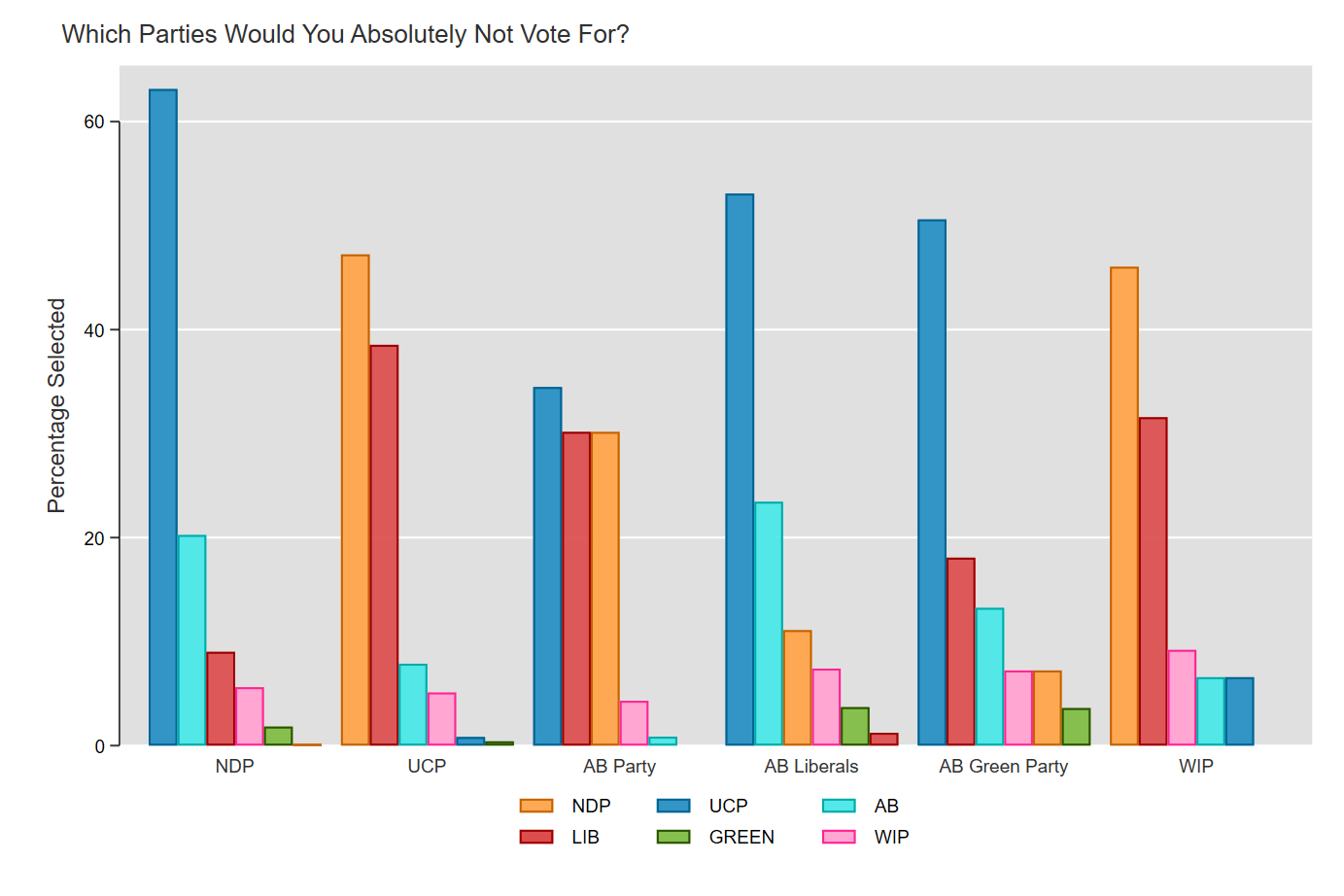

Distaste for the political “other” among NDP and UCP supporters can also be found by looking at which parties they would not vote for. Figure 16 gauges this by visualizing which political parties our respondents would not vote for and groups these by which party they support. An overwhelming majority of NDP supporters stated that they would “absolutely not” vote for the UCP. The UCP also was the most disliked party among supporters of other political parties except for Wildrose Independents UCP supporters felt an almost equal distaste for the NDP and the Liberal Party.

Of note, few Albertans indicated they would not vote for Alberta’s smaller political parties. However, it is difficult to discern whether this is genuine open-mindedness to these political parties or a preoccupation with which parties pose a credible threat to forming government.

Figure 16: Negative Partisanship

This brings us to the role of electoral expectations. Despite the UCP being the most disliked among supporters of 4 out of 6 of Alberta’s political parties, electoral predictions still favoured the United Conservatives (Figure 17). Just over half of Albertan felt the UCP were poised to win the election, compared to just under 40% who felt the NDP would unseat the UCP incumbents. It is difficult to determine the impact of these expectations on voter behaviour. That barely half the electorate accurately predicted the outcome reinforces the closeness of the election.

The New Democrats’ inability to project themselves as a viable and feasible government in waiting likely contributed to their defeat.

Figure 17: Election Predictions

While the UCP was the most disliked party across the majority of Alberta’s political parties, the NDP failed to position itself as a viable alternative among those they needed support from the most: stalwart UCP voters. Few decided UCP voters viewed the NDP as a viable alternative.

MODELLING VOTE CHOICE

The second portion of our study analyzes which factors were most important in determining how individual voters cast their ballots. A series of logistic regression models are fit to explain the variables contributing to the likelihood of casting a vote for the NDP versus a vote for the UCP.

Demographic Modelling

We begin with demographics. Figure 18 illustrates how demographic traits impacted the likelihood of voting for the UCP or the NDP.

One can think of logistic regression as a way of predicting the probability of an outcome taking place — in our case, this is either a vote for the NDP or the UCP. Our coefficients (the bars plotted in Figure 18) show whether this outcome is less likely (for values below zero) and more likely (for values above zero). In other words, the further a bar goes to the left, the less likely a person with that characteristic would vote for that particular party; the further to the right, the more likely.

We also attach asterisks to the left of the variable names in our figures. Where variables lack an asterisk, we cannot conclude that the relationship found in our sample of respondents exists in the broader population. That is, the effect of this variable is not statistically significant (regardless of the size of the bars). Included among these factors are union membership, marital status and children, and immigrant status.

Figure 18: Demographic Variables and Vote Likelihood

From Figure 18, we can build a generalized demographic profile for NDP and UCP:

A typical NDP voter is likely to work in the public sector, have more years of schooling, live in a larger urban area, have a lower income, are more secular, and are female.

A typical UCP voter is essentially the opposite. They are likely working in the private sector, have fewer years of schooling, live in a smaller rural area or small town, have a higher income, are religious, and are male.

Demographics alone cannot tell the full story. Figure 19 retains our strongest demographic variables as controls and introduces several attitudinal factors to account for how feelings may impact vote choice.

Figure 19: Demographic and Attitudinal Model

A brief description of these variables are offered below. Appendix A describes their components in more detail.

Populist feelings account for the extent to which voters feel that the people should be making political decisions and that the will of the majority ought to outweigh others.

Economic justice is another scale that measures whether respondents wanted to see more wealth distribution in Alberta. This includes whether the government should guarantee a certain standard of living, how much should be done to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor, and that the rich and powerful are the primary beneficiaries of our politics.

Sense of national identity measures if our respondents identified more as Canadian than as Albertan.

Regionalism combines measures that gauged how respondents felt about Alberta’s place in Confederation. Namely, whether they felt equalization was fair and whether other provinces are looked after before Alberta.

Anti-establishment measures how respondents felt about how Albertan politicians represent the people. It comprises two components: (1) the extent to which respondents felt Alberta politicians are “the main problem”, and (2) the extent to which respondents felt Albertan politicians “lose touch with the people” once elected.

Media confidence is the extent to which respondents felt confident in the media.

Exclusionary attitudes examine several variables about whether immigrants harm our culture, security, and economy. But also includes how respondents felt about the impact of new lifestyles, equal rights, and the decline of family values in society.

Social capital measures the number of close friends each respondent has, and the number of friends with different ethnic backgrounds.

Age in place is a measure of how long respondents have lived in their community.

Lastly, oil protectionism accounts for whether respondents feel more should be done to prioritize Alberta’s oil and gas industry.

After accounting for these attitudes, many demographic variables are no longer significant predictors of voting. Only sector of work, education, and degree of urbanization remain significant predictors of vote likelihood. In other words, the attitudes held by Albertans were seemingly more important than demographic characteristics.

Figure 19 displays which variables positively or negatively impacted voting NDP or UCP, holding all other factors constant. Respondents who voted NDP were likelier to hold negative perceptions of Alberta’s politicians and feel that Alberta’s political establishment is out of touch with the people. Also, they were more likely to hold a stronger sense of economic justice, were more trusting in the media, and felt a greater attachment to Canada than Alberta.

Conversely, UCP voters were more likely to hold exclusionary attitudes, feel more should be done for Alberta’s oil and gas industry, were more attached to Alberta than Canada, and were much less confident in the media. Crucially, unlike NDP supporters, UCP supporters were much less likely to feel disaffection with the Alberta political establishment (Figure 20).

Figure 20: Anti-Establishment Attitudes and Vote Likelihood

Figure 21 illustrates the effect of select variables on vote likelihood. The top left panel in Figure 21 conveys that those who felt there should be less should be done to prioritize Alberta’s oil industry were more likely to vote NDP; as respondents scored higher on the oil protectionism scale, their likelihood of voting NDP decreased. Comparatively, as respondents rated higher on the oil protectionism scale, their likelihood of voting for the UCP increased.

The top right panel plots the effect of identifying more as a Canadian or an Albertan on vote likelihood. Here identifying more as a Canadian increases the likelihood of voting for the NDP and decreases the likelihood of voting for the UCP. The reverse is also true; those who identified more as Albertan had an increased likelihood of voting for the UCP.

The bottom panel demonstrates the effect of holding exclusionary attitudes on vote choice. Here those with greater scepticism of immigrants and new lifestyles have an increased likelihood of voting for the UCP. In comparison, those more receptive to new immigrants and lifestyles (low score on the exclusionary scale) have a greater likelihood of voting for the NDP.

Figure 21: Predictive Margins Vote Likelihood (95% CI) Select Variables

VOTE SWITCHERS

Lastly, we searched for reasons why some Albertans changed their minds about who to support. While some analyses examine vote switching from one election to another, the C-Dem dataset allows us the rare opportunity to track the attitudes of the same people before the election (the campaign period survey) and afterwards (post-election survey). We also were able to obtain data on how folks voted in the previous election.

Figure 22 illustrates how vote preferences changed between election years. While the majority of NDP and UCP supporters remained consistent with their vote from 2019, among our sample, just under 20% of those who voted UCP in 2019 instead voted NDP in 2023. This remains consistent with findings from earlier, which revealed that roughly 20% of ideologically right-leaning Albertan’s voted for the NDP. As well, the NDP made gains among those who had previously voted for the Alberta Liberals, Green Party, and Alberta Party. This reinforces perceptions that the New Democrats have consolidated the left and centre-left vote in the province.

Figure 22: Vote Change 2019 to 2023

Most NDP and UCP voters did not switch their vote from their stated preference in the pre-election survey. In our sample, less than 5% of voters switched between the two major parties combined. However, roughly 20% of respondents who supported political parties outside Alberta’s two mainstream parties did switch to either the NDP or UCP on election day (Figure 23).

Figure 23: Vote Switching In Campaign Period

Figure 24 shows which issues were most important to NDP and UCP vote switchers. Findings are in line with which party was seen to best handle either healthcare (NDP) or the economy (UCP). There is a noticeable difference in how the issue of the economy impacted swing voter choice. While 35% of people who changed their vote to the UCP cited the economy as the most important issue, less than 10% of NDP switchers were “economic voters”. In other words, swing voters that prioritized the economy overwhelmingly ended up voting for the UCP.

The proportion of NDP swing voters that identified “leadership” as an issue was also ten percentage points higher than UCP swing voters. Leadership in this case primarily concerned dissatisfaction with Danielle Smith (NDP switch) or Rachel Notley (UCP switch); some expressed dismay with provincial leadership in general. Regardless, roughly 15% of NDP switchers were concerned with the province’s leadership, compared to only 5% of UCP switchers.

Figure 24: Vote Switching By Most Important Issue

Few Albertans were swayed within the campaign period to switch their vote between the two major parties. Supporters of other political parties who ultimately voted NDP prioritized healthcare, while those who ended up voting UCP favoured the economy.

CONCLUSION

While this study is not exhaustive, it has provided some insights into why Alberta’s recent election was so close. In many respects, the election boiled down to the UCP being favoured among voters that prioritized the economy and affordability (Figure 3). While the NDP did come out ahead in the handling of healthcare, education, climate, and leadership, none of these, except for healthcare, were the primary concerns of Albertans. Crucially, the UCP came out slightly ahead among our respondents when it came to handling the affordability crisis, which was the second most important issue among respondents. Coupled with a dominant lead in our third most important issue, the economy, the UCP appeared to hold an issue advantage when it came to what many swing voters cared about the most.

Issue advantages aside, why was the election so close? In our analysis, several factors seemed to be at play. First, Danielle Smith and the UCP, more generally, made an overall worse impression on voters. Even in less urbanized areas, a traditional stronghold of Alberta’s conservatives, Smith was not overwhelmingly popular with voters (Figures 5 and 7).

Second, the Alberta NDP siphoned off a significant portion — around a quarter —of right-leaning Albertans (Figure 13) and one-in-five of those who identify as Federal Conservatives. Combined with their consolidation of the centre-left vote, these gains were enough to position the NDP as the strongest opposition party in Alberta history.

Third, across all voters, the proportion of Albertans who felt the economy and their finances had worsened under the UCP exceeded those who felt things had gotten better (Figures 10 & 12). In other words, discontent with the incumbent government likely shifted a few voters towards the NDP.

Fourth, among voter switchers, about 12% of Albertan’s shifted their vote to the NDP from other political parties, slightly exceeding those who shifted to the UCP. Those who did shift to the NDP from other parties overwhelmingly prioritized healthcare, affordability, and to a lesser extent leadership.

Lastly, the NDP overwhelmingly won over urban voters, whereas rural and small towns remained UCP strongholds (Figure 19). In fact, after accounting for political attitudes, urbanization was the only demographic variable to remain significant in our model, asides from sector of work. In terms of Alberta’s seat distribution, this gap heavily favours the UCP, which, assuming a relative sweep of the rural ridings, only requires a few seats in urban centres to form government. However, it was enough to tip several of Alberta’s big city ridings to the NDP.

Regarding political attitudes, partisanship seems to be playing an increasing role in how Albertans assess socioeconomic reality. Reflecting on Figure 9, there is a substantial gap in how NDP supporters and UCP supporters viewed the economy, the latter having a much more positive outlook. They also drastically differ in assessing how government policy has impacted the economy.

Relatedly, political attitudes, not demographics, proved to be better predictors of vote likelihood (Figure 19). For example, those disillusioned with Alberta’s political establishment were much more likely to vote NDP, whereas discontent with how Alberta is treated in Confederation (regionalism) was much more likely to vote UCP. Sometimes these attitudes can occur organically, but often they are shaped. Our analysis suggests that party identification may play a significant role in how Albertan’s form opinions on issues and assess political leaders — which ultimately impacts vote choice. However, more research must be done beyond this brief to explore this phenomenon further.

APPENDIX A