by Jared Wesley, Garin Alfaro, and Lauren Hill

The 2023 Alberta election campaign is the most hotly contested in the province’s history. Not only are the two leading parties neck and neck in the polls, but most public commentary suggests the NDP and UCP are engaging in a pitched ideological battle for the hearts and minds of voters.

Beyond the elite rhetoric and common wisdom, to what extent are Albertans actually polarized? Do residents really diverge when it comes to their ideological placements and values commitments, or are the apparent divisions in society driven by something else, like political or partisan identity?

Albertans aren’t as polarized as common wisdom suggests.

A politically polarized society is one in which people demonstrate divergent views and/or forms of identity. The greater the polarization, the more likely we are to see divisive and combative forms of competition both within, and even outside of, the domain of politics. If Alberta is, indeed, polarized, this has important implications for the functioning of democratic institutions and the level of trust among citizens and in elites.

With the widely-shared belief that polarization is reaching unprecedented levels within western democratic societies, the Common Ground team set out to investigate just how divided Albertans really are. Drawing on a variety of measures, including ideological self-placement , social distance scales, and identity markers, this brief provides an assessment of the current level of political polarization existing in Albertan society.

Ideological Polarization and Political Identity

The most common way to determine the level of political polarization in a society is by how people distribute themselves along the left-right ideological political spectrum. Polarized communities feature clusters of people at either pole of that scale.

Illustrated in Figure 1, most Albertans position themselves at or near the centre of the political spectrum. This suggests a centrist tendency among the majority of the population, with over half of them positioning themselves between 4 and 6 on a ten-point scale.

Most Albertans are centrist, placing themselves at or near the middle of the political spectrum.

When we examined a host of different sub-groups of the population, we did not see much divergence from this pattern. Figure 2 shows the ideological differences between men and women, and urban and suburban Albertans; we found similar patterns when we compared respondents according to education, income, and a host of other variables.

Only when we add partisan identification do we start to see an ideological division emerge (Figure 3). Even then, there is considerable overlap between those who identify as New Democrats and those who identify as United Conservatives, suggesting there is less ideological polarization than is typically assumed.

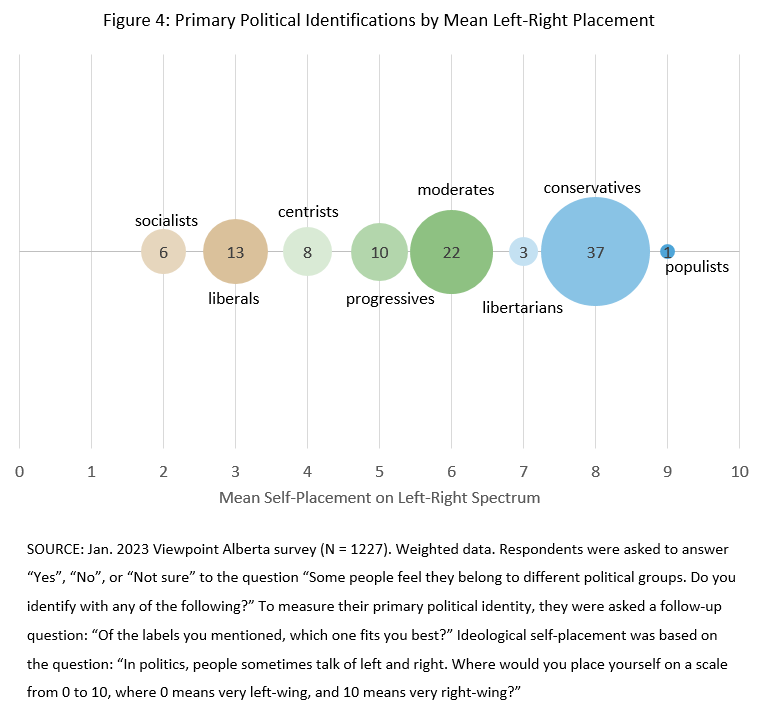

We also examined peoples’ political identities by asking respondents whether they accepted a series of labels. Figure 4 shows that the two most popular primary political self-identifications for Albertans are “conservative” (37 percent) and “moderate” (22 percent). Small-l “liberal” and “progressive” self-identifications follow at 13 percent and 10 percent respectively, while socialist, centrist, libertarian, and populist labels were far less frequent.

In a highly polarized society, an overwhelming majority of Albertans would place themselves squarely within the left and right wings of the spectrum; instead, we see nearly a third of Albertans (29 percent) classifying their primary identifications as moderate or centrist.

Albertans are as likely to identify as “moderate” or “progressive” as they are to identify as “conservative.” And they often take on several labels at once.

Indeed, when we consider political identity as more than simply a “primary” marker but rather a combination of different labels, we find that Albertans are far more diverse than polarized. Recall that we asked respondents to “check all that apply” when it came to different political identities. The most commonly chosen label was “moderate,” with over 53 percent of Albertans identifying with that term (Figure 5). While 45 percent of respondents identified as “conservative,” a nearly-identical proportion viewed themselves as “progressive” (44 percent).

In other words, political identifications are not mutually exclusive. When we also consider the other labels that Albertans chose for themselves beyond their primary identifications, a more nuanced picture emerges. Depicted in Figure 6, the majority of respondents who self-identified as primarily liberal or progressive also identified as centrists or moderates (57 percent of liberals and 98 percent of progressives). On the right, the majority of conservatives (58 percent) also identified with centrist and moderate ideological labels. This suggests that, in addition to the wider Albertan electorate, there is no overwhelming political polarization within individual ideological camps.

Perhaps most remarkable, 36 percent of progressives also identified as conservatives and nearly half (47 percent) of conservatives also described themselves as progressive. This significant overlap amounts to 82 percent of Albertans identifying with both labels, an indication that Albertan society is not effectively divided into two incompatible opposing progressive and conservative camps.

Value Polarization

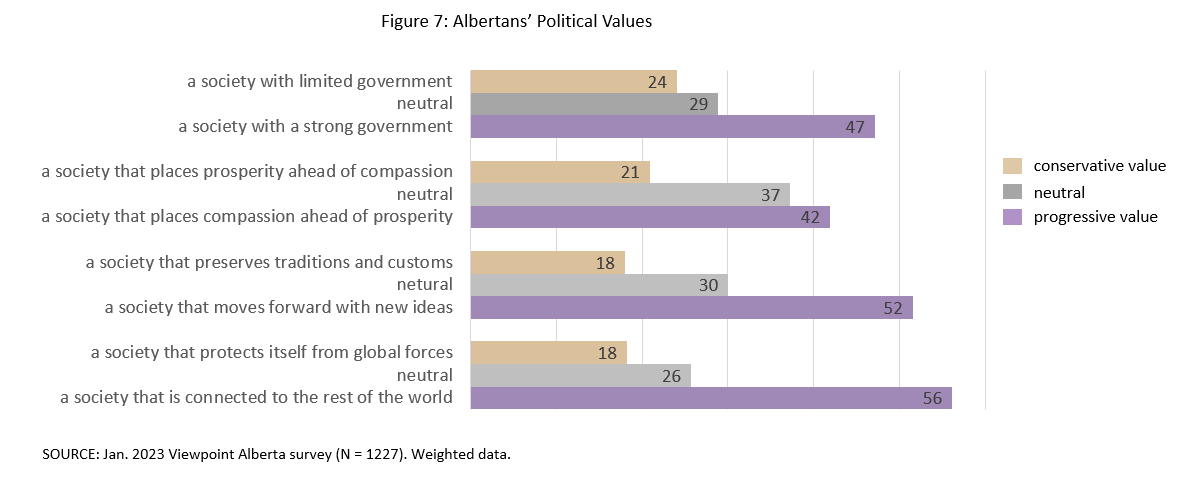

Beyond the left-right spectrum, we also employed a values-based measure to determine the extent of political polarization in Alberta. Using a scale developed through an extensive literature review and expert survey, we assessed the extent to which Albertans were “progressive” (demonstrating an affinity for strong, compassionate government that moves forward with new ideas and builds relationships outside provincial borders) versus “conservative” (preferring a limited form of government that prioritizes prosperity, tradition, and protection from outside forces).

Respondents were posed a series of four statement pairs and asked to place themselves along a 5-point sliding scale to indicate their preference between two given options (with 3 indicating a neutral preference).

When it comes to their political values, more Albertans show progressive or neutral than conservative tendencies.

Figure 7 shows the breakdown of results for each value pair. Surprisingly, given the conventional view of the province as a bastion of conservatism, Albertans were more likely to express their preference for the progressive option than the conservative one. A characteristically polarized distribution would show the vast majority of respondents situating themselves on opposite ends of the values scale, but in this case approximately one third of Albertans indicated a neutral preference on all four questions.

Figure 8 displays the composite scores on these values questions. To score a “-4” for example, the respondent must have preferred the more progressive option in all four question pairs. Consistent with the individual question responses, the index scores also show a distribution that is skewed toward a progressive values approach. Indeed, 61 percent of Albertans indicated a progressive orientation, overall, 17 percent demonstrated a balanced values approach, and 22 percent aligned with a conservative value-set.

Affective Polarization and Partisan Sorting

The preceding data suggests that the ideological positions and political values of Albertans overlap to a significant degree, with most Albertans showing an affinity for moderate, progressive, and conservative politics. In order to get a clearer understanding of how Albertans relate to each other politically however, we must consider affective polarization. This involves a combination of strong in-group affinity (for one’s own party or political group) and out-group animosity (towards one’s opponents).

Leader evaluations are one means of measuring this type of division. To the extent that one group of partisans lauds its own leader and despises its opponent’s, this could be an indication of strong in-group attachment and out-group animosity.

Figure 9 illustrates that New Democrats feel very positively about their own leader, Rachel Notley, and very negatively about Danielle Smith. Only 3 percent revealed preference for Smith over Notley, and 11 percent indicated equal preference. The same could not be said of UCP identifiers, however. A full 19 percent of United Conservatives preferred Notley over their own party leader, illustrating a surprising level of inter-party agreement. These results demonstrate that even in party leader preferences, Albertans are not diametrically opposed to one another when it comes to their evaluation of the two front-running leaders.

Many Albertans share a preference for Notley over Smith.

To further measure the level of affective polarization in Alberta, we examined the level of partisan sorting: the extent to which residents align their partisan identifications with their ideological and values orientations.

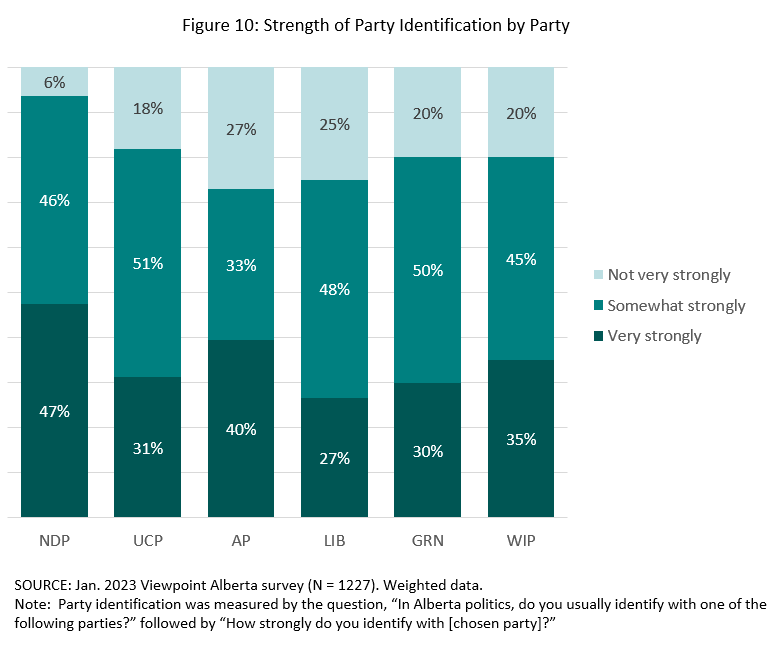

We begin by considering the strength of partisan attachments. The assumption is that the more strongly Albertans identify with their chosen political parties, the more bias they will exhibit against those with contrasting political identifications. Figure 10 shows the strength of partisan attachments among Albertans that identify primarily with the UCP, NDP, Alberta Party (AP), Liberal Party of Alberta (LIB), Green Party of Alberta (GRN), and Wildrose Independence Party (WIP). Figure 7 displays the proportions of Alberta’s population made up of strong, medium, and weak identifiers of the UCP, NDP, and others. Fewer than half of the people in each camp identify with their chosen parties very strongly. NDP partisans expressed the strongest party attachments among all groups, with 47 percent of respondents self-reporting very strong identifications.

Figure 11 also indicates that strong UCP and NDP identifiers make up only a quarter of the population. These low figures would predict a low level of affective polarization, though strong partisan identities are only one part of the picture.

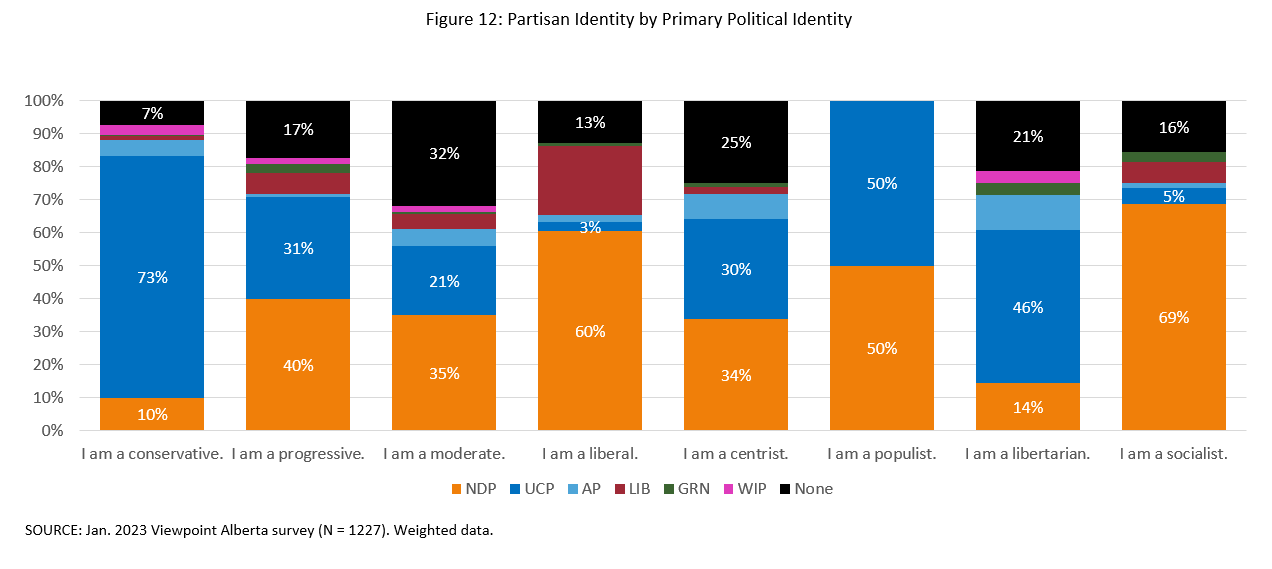

Another predictor of affective polarization is the alignment of partisan and ideological identities among party cohorts, known as partisan sorting. In a society with high affective polarization, we would expect the members of small-c conservative political parties to identify almost exclusively with traditional right-wing ideologies (namely conservatism and libertarianism) and left-wing partisans to identify almost exclusively with left-wing ideologies (including liberalism, progressivism, and socialism). When ideology and partisanship are neatly sorted, political parties become more homogenous and the exposure of partisans to different ideas is reduced. Polarization increases accordingly.

About a quarter of the electorate consists of die-hard New Democrats and United Conservatives. Most Albertans have a looser attachment to parties.

Partisan sorting in Alberta is relatively limited. Figure 12 illustrates the distribution of primary ideological identities among Alberta’s major political parties. Interestingly, only 40 percent of progressives self-reported as belonging to the NDP, with 31 percent belonging to the UCP. This indicates that the progressive camp has not undergone effective partisan sorting. On the other side of the spectrum, nearly 10 percent of conservatives (Alberta’s largest primary ideological identification at 37 percent) belong to the NDP. Finally, the percentage of centrist and moderate respondents that belong to the NDP and UCP are very similar.

Figure 13 depicts the flipside of partisan sorting by representing the ideological makeup of each party. A combined 71 percent of UCP identifiers consider themselves primarily as conservative or libertarian, while self-described liberals, progressives, and socialists make up only 51 percent of New Democrats.

Still, the fact that 10 percent of UCP identifiers describe themselves as primarily ascribing to left-wing political ideologies (with 13 percent of NDP identifiers being self-described conservatives or libertarians) indicates that neither partisan camp has undergone complete partisan sorting.

Parties in Alberta are an eclectic mix of different political communities.

Finally, the large numbers of moderates and centrists that belong to all of Alberta’s major parties (33 percent and 19 percent of NDP and UCP identifiers respectively), including non-identifiers, also suggest a relatively high degree of inter-ideological contact across party boundaries. These findings suggest lower levels of inter-party animosity and bias.

We can also assess party identifiers according to their value-orientations (Figures 14 and 15). Among those that demonstrate a progressive-values approach, 38 and 31 percent identify with NDP and UCP, respectively. Over one-fifth of respondents (21 percent) that demonstrated a conservative-values approach align themselves with the NDP. Over half of UCP identifiers (51 percent) prefer a progressive-values approach.

These results all point to an Alberta where residents who hold contradictory value-orientations continue to congregate within the same political parties, a factor that should minimize affective polarization.

Social Distance and Factionalism in Alberta

Lastly, we investigated the extent to which political divisions in Alberta extended into the social realm, and the extent to which they might threaten the province’s democratic foundations.

First, we employed the Bogardus Social Distance Scale (BSDS), which measures the level of animosity between groups by asking respondents whether they would be comfortable entering into a series of relationships of increasing social proximity with people from other groups. After identifying their primary ideological and partisan identifications, the Viewpoint Alberta survey asked Albertans to place themselves along a sliding scale that included five hypothetical social relationships of increasing intimacy, which then allowed us to identify their level of out-group animosity.

New Democrats and United Conservatives prefer to distance themselves from each other.

Figure 16 illustrates the results collected from UCP and NDP identifiers. Only 7 percent of NDP identifiers would be comfortable with a United Conservative marrying into their immediate family, with a UCP identifier being twice as likely to be comfortable with a New Democrat in this same relationship. An additional 13 percent of NDP identifiers would be willing to have a United Conservative as a friend, and 16 percent of UCP identifiers would welcome a New Democrat as a friend. Nearly half (45 percent) of NDP identifiers would only be comfortable having a United Conservative as a fellow Canadian (but not in any of the other relationships), compared to 34 percent of UCP identifiers regarding a New Democrat.

All of this indicates that NDP identifiers express more out-group animosity than UCP identifiers. Additionally, contrary to our expectations, these BSDS results suggest a significantly high level of affective polarization among members of Alberta’s two largest political parties.

This said, partisans are not exactly comfortable with having close relationships with people from their own party. Only 39 percent of NDP identifiers and 26 percent of UCP identifiers indicated that they would be comfortable with their fellow partisans marrying into their immediate family (not shown). Additionally, 22 percent of NDP identifiers and 27 percent of UCP identifiers were only comfortable having their fellow partisans as fellow Canadians. These intra-party findings place some nuance on the conclusion that Albertans are affectively polarized.

Lastly, we assembled an index to measure the level of factionalism in Alberta politics. Elsewhere, this sort of deep-seated animosity among groups is often labeled “tribalism” – a term we avoid due to its pejorative connotations for people in Indigenous and Black communities. We prefer “factionalism,” tracing its origins to Alexander Hamilton’s famous writings in The Federalist Papers.

To Hamilton, democratic institutions must be built to protect against the polarization of society into enemy camps, “united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community” (1787).

We identified factionalist tendencies of Albertans through six questions that asked respondents to indicate their preference between two options related to elections and governance (Figure 17). Factional responses show an inclination towards protectionist political activity which, in our questions, are reflected in a desire to monopolize political power in the hands of one’s favoured party. Factionalism scores are thus a suitable measure of affective polarization because they relate to the level of trust that one political group displays towards another.

Factionalism appears to be taking root in some Alberta communities.

Albertans do demonstrate some factionalist tendencies, according to these measures. While a majority of residents feel that politicians should concede defeat if election authorities decide they have lost and that election rules should be agreed upon by all parties, fully one-third of Albertans did not fully agree with those statements. The same proportion (33 percent) felt that “elections should be like wars between parties,” slightly more than the share who thought campaigns should be “debates between friends” (30 percent). United Conservatives were slightly more factionalist than New Democrats on some of these measures, with 38 percent of UCP identifiers seeing elections “like war,” 41 percent feeling that “my party should win every election,” and 26 percent agreeing that “my party should control all government decisions” (not shown).

Figure 18 presents the percentage of respondents by their Factionalism Index score. To receive an index score of 6, a respondent had to choose the factional option on all six questions. To receive a 0, a respondent had to choose the non-factionalist option on all six questions. Over two-thirds (68 percent) of all respondents had a factionalism score of 0 or 1, including 62 percent of NDP identifiers and 59 percent of UCP identifiers. Once again it appears that most Albertans, regardless of primary partisan identities, are less polarized than common wisdom suggests.

Concluding Thoughts

Overall, this study suggests Albertans are not as polarized as common wisdom and popular commentary suggests. To the extent that polarization exists – particularly among strong New Democrats and United Conservatives – this is driven more by partisanship than deeper values and ideological differences.

Beginning with ideological and values-based measures, we found that the identifications and political preferences of Albertans overlap to a significant degree. Furthermore, moderate and centrist positions continue to predominate among Albertans, regardless of their primary identifications. These results suggest that Albertans have a lot in common, with plenty of political common ground to accommodate mutual understanding and cooperation.

Indeed, we found that Albertans score relatively low on measures of partisan sorting and factionalism. They prefer political power-sharing and compromise over more combative forms of politics. All of this suggests that Albertans have the capacity and desire to engage with each other in constructive ways, at least at the level of resident-to-resident.

Methodology

The Viewpoint Alberta Survey was conducted between January 17 and February 9, 2023. The survey was deployed online by Leger. A copy of the survey questions can be found here: https://bit.ly/3Tk8Hpl. Leger co-ordinates the survey with an online panel system that targets registered panelists that meet the demographic criteria for the survey. Survey data is based on 1,227 responses with a 15-minute average completion time. Split samples were employed for certain survey questions. The Viewpoint Alberta Survey was led by co-principal investigators Michelle Maroto, Feodor Snagovsky, Jared Wesley, and Lisa Young. It was funded in part by a grant from the Kule Institute for Advanced Study (KIAS) at the University of Alberta.

So many more rural voters have progressive views? I know my parents, still on the farm, do. They are frustrated by those in their community voting against their best interests, particularly regarding health care, pensions, and strong government. They are extremely happy to have a strong opposition.